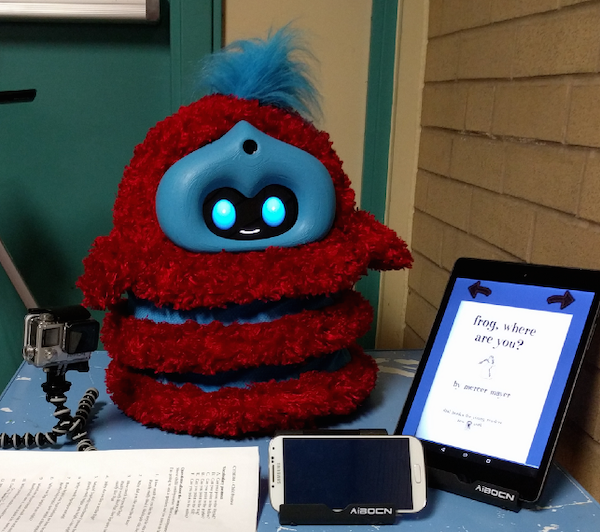

Tega sits at a school, ready to begin a storytelling activity with kids!

Last spring, you could find me every morning alternately sitting in a storage closet, a multipurpose meeting room, and a book nook beside our fluffy, red and blue striped robot Tega. Forty-nine different kids came to play storytelling and conversation games with Tega every week, eight times each over the course of the spring semester. I also administered pre- and post-assessments to find out what kids thought about the robot, what they had learned, and what their relationships with the robot were like.

Suffice to say, I spent a lot of time in that storage closet.

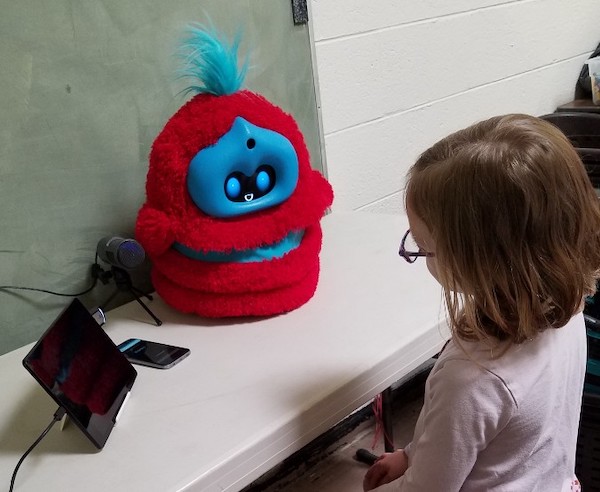

A child talks with the Tega robot.

Studying how kids learn with robots

The experiment I was running was, ostensibly, straightforward. I was exploring a theorized link between the relationship children formed with the robot and children's engagement and learning during the activities they did with the robot. This was the big final piece of my dissertation in the Personal Robots Group. My advisor, Cynthia Breazeal, and my committee, Rosalind Picard (also of the MIT Media Lab) and Paul Harris (Harvard Graduate School of Education), were excited to see how the experiment turned out, as were some of our other collaborators, like Dave DeSteno (Northeastern University), who have worked with us on quite a few social robot studies.

In some of those earlier studies, as I've talked about before, we've seen that the robot's social behaviors—like its nonverbal cues (such as gaze and posture), its social contingency (e.g., using appropriate social cues at the right times), and its expressivity (such using an expressive voice versus a flat and boring one)—can affect how much kids learn, how engaged they are in learning activities, and their perception of the robot's credibility. Kids frequently treat the robot as something kind of like a friend and use a lot of social behaviors themselves—like hugging and talking; sharing stories; showing affection; taking turns; mirroring the robot's behaviors, emotions, and language; and learning from the robot like they learn from human peers.

Five years of looking at the impact of the robot's social behaviors hinted to me that there was probably more going on. Kids weren't just responding to the robot using appropriate social cues or being expressive and cute. They were responding to more stuff—relational stuff. Relational stuff is all the social behavior plus more stuff that contributes to building and maintaining a relationship, interacting multiple times, changing in response to those interactions, referencing experiences shared together, being responsive, showing rapport (e.g., with mirroring and entrainment), and reciprocating behaviors (e.g., helping, sharing personal information or stories, providing companionship).

While the robots didn't do most of these things, whenever they used some (like being responsive or personalizing behavior), it often increased kids' learning, mirroring, and engagement.

So... what if the robot did use all those relational behaviors? Would that increase children's engagement and learning? Would children feel closer to the robot and perceive it as a more social, relational agent?

I created two versions of the robot. Half the kids played with the relational robot: the version that used all the social and relational behaviors listed above. For example, it mirrored kids' pitch and speaking rate. It mirrored some emotions. It tracked activities done together, like stories told, and referred to them in conversation later. It told personalized stories.

The other half of the kids played with the not-relational robot—it was just as friendly and expressive, but didn't do any of the special relational stuff.

Kids played with the robot every week. I measured their vocabulary learning and their relationships, looked at their language and mirroring of the robot, examined their emotions during the sessions, and more. From all this data, I got a decent sense of what kids thought about the two versions of the robot, and what kind of effects the relational stuff had.

In short: The relational stuff mattered.

Relationships and learning

Kids who played with the relational robot rated it as more human-like. They said they felt closer to it than kids who played with the not-relational robot, and disclosed more information (we tend to share more with people we're closer to). They were more likely to say goodbye to the robot (when we leave, we say goodbye to people, but not to things). They showed more positive emotions. They were more likely to say that playing with the robot was like playing with another child. They also were more confident that the robot remembered them, frequently referencing relational behaviors to explain their confidence.

All of this was evidence that the robot's relational behaviors affected kids' perceptions of it and kids' behavior with it in the expected ways. If a robot acted more in more social and relational ways, kids viewed it as more social and relational.

Then I looked at kids' learning.

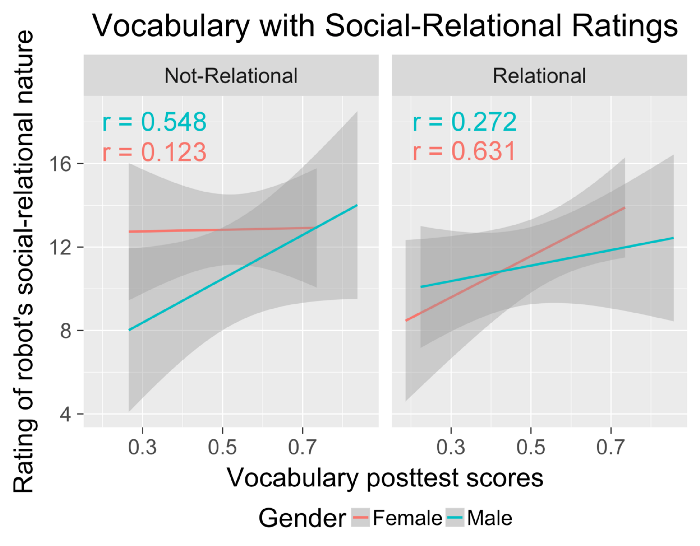

I found that kids who felt closer to the robot, rated it as more human-like, or treated it more socially (like saying goodbye) learned more words. They mirrored the robot's language more during their own storytelling. They told longer stories. All these correlations were stronger for kids who played with the relational robot—meaning, in effect, that kids who had a stronger relationship with the robot learned more and demonstrated more behaviors related to learning and rapport (like mirroring language). This was evidence for my hypotheses that the relationships kids form with peers contribute to their learning.

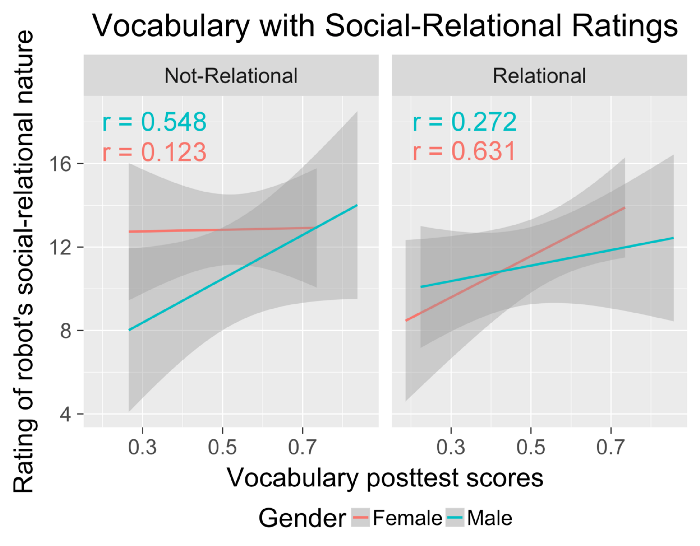

Children who rated the robot as more of a social-relational agent also scored higher on the vocabulary posttest.

This was an exciting finding. There are plenty of theories about how kids learn from peers and how peers are really important to kids' learning (famous names in the subject include Piaget, Vygotsky, and Bandura), but there's not as much research looking at the mechanisms that influence peer learning. For example, I'd found research showing that kids' peers can positively affect their language learning... but not why they could. Digging into the literature further, I'd found one recent study linking learning to rapport, and several more showing links between an agent's social behavior and various learning-related emotions (like increased engagement or decreased frustration), but not learning specifically. I'd seen some work showing that social bonds between teachers and kids could predict academic performance—but that said nothing about peers.

In exploring my hypotheses about kids' relationships and learning, I also dug into some previously-collected data to see if there were any of the same connections. Long story short, there were. I found similar correlations between kids' vocabulary learning, emulation of the robot's language, and relationship measures (such as ratings of the robot as a social-relational agent and self-disclosure to the robot).

All in all, I found some pretty good evidence for my hypothesized links between kids' relationships and learning.

I also found some fascinating nuances in the data involving kids' gender and their perception of the robot, which I'll talk about in a later post. And, of course, whenever we talk about technology, ethical concerns abound, so I'll talk more about that in a later post, too.

—

This article originally appeared on the MIT Media Lab website, February, 2019