Relational Robots

My latest research in Cynthia Breazeal's Personal Robots Group has been on relational technology.

By relational, I mean technology that is designed to build and maintain long—term, social—emotional relationships with users. It's technology that's not just social—it's more than a digital assistant. It doesn't just answer your questions, tell jokes on command, or play music and adjust the lights. It collects data about you over time. It uses that data to personalize its behavior and responses to help you achieve long term goals. It probably interacts using human social cues so as to be more understandable and relatable—and furthermore, in areas such as education and health, positive relationships (such as teacher—student or doctor—patient) are correlated with better outcomes. It might know your name. It might try to cheer you up if it detects that you're looking sad. It might refer to what you've done together in the past or talk about future activities with you.

Relational technology is new. Some digital assistants and personal home robots on the market have some features of relational technology, but not all the features. Relational technology is still a research idea more than a commercial product. Which means right now, before it's on the market, is the exact right time to talk about how we ought to design relational technology.

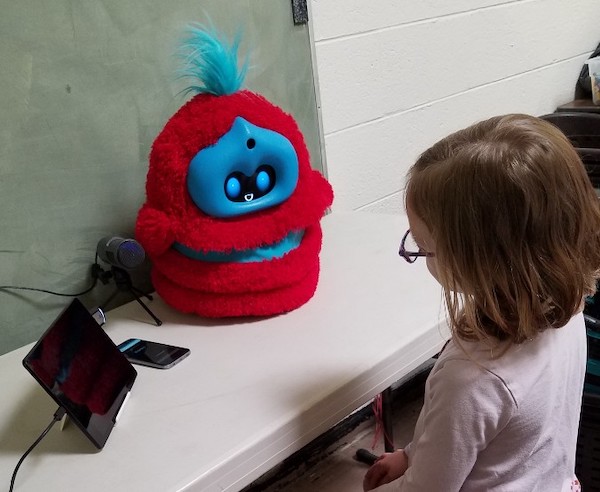

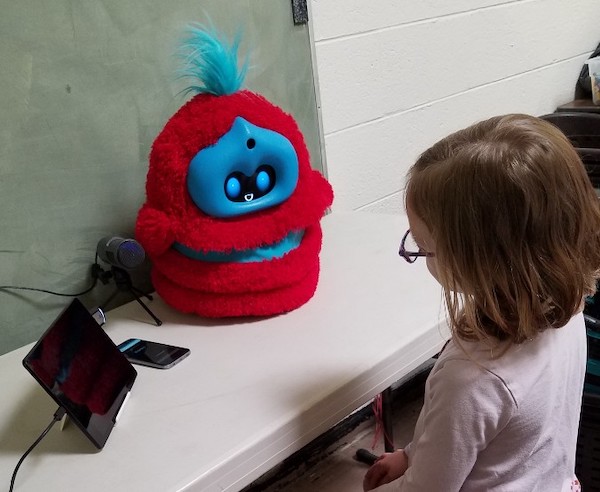

As part of my dissertation, I performed a three-month study with 49 kids aged 4-7 years. All the kids played conversation and storytelling games with a social robot. Half the kids played with a version of the robot that was relational, using all the features of relational technology to build and maintain a relationship and personalize to individual kids. It talked about its relationship with the child and disclosed personal information about itself; referenced shared experiences (such as stories told together); used the child's name; mirrored the child's affective expressions, posture, speaking rate, and volume; selected stories to tell based on appropriate syntactic difficulty and similarity of story content to the child's stories; and used appropriate backchanneling actions (such as smiles, nods, saying "uh huh!"). The other half of the kids played with a not-relational robot that was just as friendly and expressive, but without the special relational stuff.

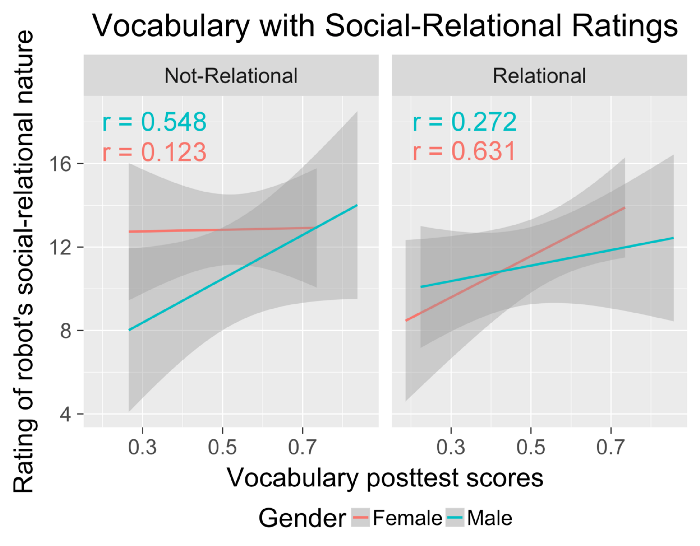

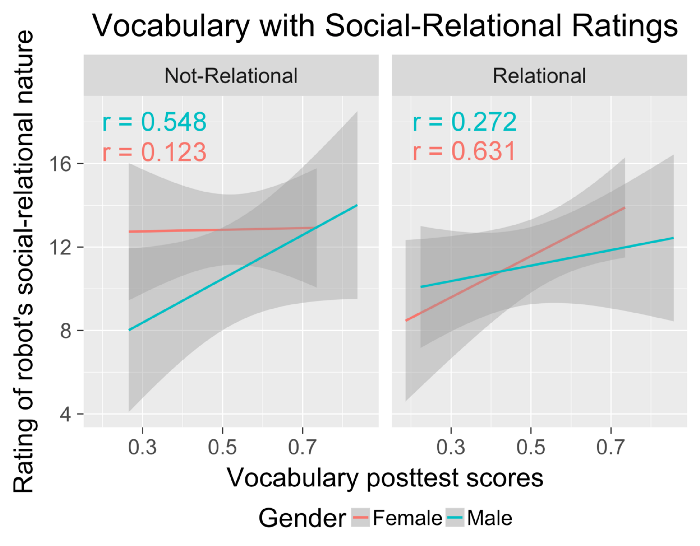

Besides finding some fascinating links between children's relationships with the robot, their perception of it as a social-relational agent, their mirroring of the robot's behaviors, and their language learning, I also found some surprises. One surprise was that we found gender differences in how kids interacted with the robot. In general, boys and girls treated the relational and not-relational robots differently.

Boys and girls treated the robots differently

Girls responded positively to the relational robot and less positively to the not-relational robot. This was the pattern I expected to see, since the relational robot was doing a lot more social stuff to build a relationship. I'd hypothesized that kids would like the relational robot more, feel closer to it, and treat it more socially. And that's what girls did. Girls generally rated the relational robot as more of a social-relational agent than the not-relational robot. They liked it more and felt closer to it. Girls often mirrored the relational robot's language more (we often mirror people more when we feel rapport with them), disclosed more information (we share more with people we're closer to), showed more positive emotions, and reported feeling more comfortable with the robot. They also showed stronger correlations between their scores on various relationship assessments and their vocabulary learning and vocabulary word use, suggesting that they learned more when they had a stronger relationship.

Children who rated the robot as more of a social-relational agent also scored higher on the vocabulary posttest—but this trend was stronger for girls than for boys.

Boys showed the opposite pattern. Contrary to my hypotheses, boys tended to like the relational robot less than the not-relational one. They felt less close to it, mirrored it less, disclosed less, showed more negative emotions, showed weaker correlations between their relationship and learning (but they did still learn—it just wasn't as strongly related to their relationship), and so forth. Boys also liked both robots less than girls did. This was the first time we'd seen this gender difference, even after observing 300+ kids in 8+ prior studies. What was going on here? Why did the boys in this study react so differently to the relational and not—relational robots?

I dug into the literature to learn more about gender differences. There's actually quite a bit of psychology research looking at how young girls and boys approach social relationships differently (e.g., see Joyce Benenson's awesome book Warriors and Worriers: The Survival of the Sexes). For example, girls tend to be more focused on individual relationships and tend to have fewer, closer friends. They tend to care about exchanging personal information and learning about others' relationships and status. Girls are often more likely to try to avoid conflict, more egalitarian than boys, and more competent at social problem solving.

Boys, on the other hand, often care more about being part of their peer group. They tend to be friends with a lot of other boys and are often less exclusive in their friendships. They frequently care more about understanding their skills relative to the skills other boys have, and care less about exchanging personal information or explicitly talking about their relationships.

Of course, these are broad generalizations about girls versus boys that may not apply to any particular individual child. But as generalizations, they were often consistent with the patterns I saw in my data. For example, the relational robot used a lot of behaviors that are more typical of girls than of boys, like explicitly sharing information about itself and talking about its relationship with the child. The not-relational robot used fewer actions like these. Plus, both robots may have talked and acted more like a girl than a boy, because its speech and behavior were designed by a woman (me), and its voice was recorded by a woman (shifted to a higher pitch to sound like a kid). We also had only women experimenters running the study, something that has varied more in prior studies.

I looked at kids' pronoun usage to see how they referred to the relational versus not-relational robot. There wasn't a big difference among girls; most of them used "he/his." Boys, however, were somewhat more likely to use "she/her." So one reason boys might've reacted less positively to it because they saw it as more of a girl, and they preferred to play with other boys.

We need to do follow-up work to examine whether any of these gender-related differences were actually causal factors. For example, would we see the same patterns if we explicitly introduced the robot as a boy versus as a girl, included more behaviors typically associated with boys, or had female versus male experimenters introduce the robot?

Designing Relational Technology

These data have interesting implications for how we design relational technology. First, the mere fact that we observed gender differences means we should probably start paying more attention to how we design the robot's gender and gendered behaviors. In our current culture and society, there are a range of behaviors that are generally associated with masculine versus feminine, male versus female, boys versus girls. Which means that if the robot acts like a stereotypical girl, even if you don't explicitly say that it is a girl, kids are probably going to treat it like a girl. Perhaps this might change if children are concurrently taught about gender and gender stereotypes, but there are a lot of open questions here and more research is needed.

One issue is that you may not need much stereotypical behavior in a robot to see an effect—back in 2009, Mikey Siegel performed a study in the Personal Robots group that compared two voices for a humanoid robot. Study participants conversed with the robot, and then the robot solicited a donation. Just changing the voice from male to female affected how persuasive, credible, trustworthy, and engaging people found the robot. Men, for example, were more likely to donate money to the female robot, while women showed little preference. Most participants rated the opposite sex robot as more credible, trustworthy, and engaging.

As I mentioned earlier, this was the first time we'd seen these gender differences in our studies with kids. Why now, but not in earlier work? Is the finding repeatable? A few other researchers have seen similar gender patterns in their work with virtual agents...but it's not clear yet why we see differences in some studies but not others.

What gender should technology have—if any?

Gendering technological entities isn't new. People frequently assign gender to relatively neutral technologies, like robot vacuum cleaners and robot dogs—not to mention their cars! In our studies, I've rarely seen kids not ascribe gender to our fluffy robots (and it has varied by study and by robot what gender they typically pick). Which raises the question of what gender a robot should be—if any? Should a robot use particular gender labels or exhibit particular gender cues?

This is largely a moral question. We may be able to design a robot that acts like a girl, or a boy, or some androgynous combination of both, and calls itself male, female, nonbinary, or any number of other things. We could study whether a girl robot, a boy robot, or some other robot might work better when helping kids with different kinds of activities. We could try personalizing the robot's gender or gendered behaviors to individual children's preferences for playmates.

But the moral question, regardless of whatever answers we might find regarding what works better in different scenarios or what kids prefer, is how we ought to design gender in robots. I don't have a solid recommendation on that—the answer depends on what you value. We don't all value the same things, and what we value may change in different situations. We also don't know yet whether children's preferences or biases are necessarily at odds with how we might think we should design gender in robots! (Again: More research needed!)

Personalizing robots, beyond gender

A robot's gender may not be a key factor for some kids. They may react more to whether the robot is introverted versus extraverted, or really into rockets versus horses. We could personalize other attributes of the robot, like aspects of personality (such as extraversion, openness, conscientiousness), the robot's "age" (e.g., is it more of a novice than the child or more advanced?), whether it uses humor in conversation, and any number of other things. Furthermore, I'd expect different kids to treat the same robot differently, and to frequently prefer different robot behaviors or personalities. After all, not all kids get along with all other kids!

However, there's not a lot of research yet exploring how to personalize an agent's personality, its styles of speech and behavior, or its gendered expressions of emotions and ideas to individuals. There's room to explore. We could draw on stereotypes and generalizations from psychological research and our own experiences about which kids other kids like playing with, how different kids (girls, boys, extroverts, etc.) express themselves and form friendships, or what kinds of stories and play boys or girls prefer (e.g., Joyce Benenson talks in her book Warriors and Worriers about how boys are more likely to include fighting enemies in their play, while girls are more likely to include nurturing activities).

We need to be careful, too, to consider whether making relational robots that provide more of what the child is comfortable with, more of what the child responds to best, more of the same, might in some cases be detrimental. Yes, a particular child may love stories about dinosaurs, battles, and knights in shining armor, but they may need to hear stories about friendship, gardening, and mammals in order to grow, learn, and develop. Children do need to be exposed to different ideas, different viewpoints, and different personalities with whom they must connect and resolve conflicts. Maybe the robots shouldn't only cater to what a child likes best, but also to what invites them out of their comfort zone and promotes growth. Maybe a robot's assigned gender should not reinforce current cultural stereotypes.

Dealing with gender stereotypes

A related question is whether, given gender stereotypes, we could make a robot appear more neutral if we tried. While we know a lot about what behaviors are typically considered feminine or masculine, it's harder to say what would make a robot come across as neither a boy nor a girl. Some evidence suggests that girls and women are culturally "allowed" to display a wider range of behaviors and still be considered female than are boys, who are subject to stronger cultural rules about what "counts" as appropriate masculine behavior (Joyce Benenson talks about this in her book that I mentioned earlier). So this might mean that there's a narrower range of behaviors a robot could use to be perceived as more masculine... and raises more questions about gender labels and behavior. What's needed to "override" stereotypes? And is that different for boys versus girls?

One thing we could do is give the robot a backstory about its gender or lack thereof. The story the robot tells about itself could help change children's construal of the robot. But would a robot explicitly telling kids that it's nonbinary, or that it's a boy or a girl, or that it's just a robot and doesn't have a gender be enough to change how kids interact with it? The robot's behaviors—such as how it talks, what it talks about, and what emotions it expresses—may "override" the backstory. Or not. Or only for some kids. Or only for some combinations of gendered behaviors and robot claims about its gender. These are all open empirical questions that should be explored while keeping in mind the main moral question regarding what robots we ought to be designing in the first place.

Another thing to explore in relation to gender is the robot's use of relational behaviors. In my study, I saw the robot's relational behaviors made a bigger difference for girls than for boys. Adding in all that relational stuff made girls a lot more likely to engage positively with the robot.

This isn't a totally new finding—earlier work from a number of researchers on kids' interactions with virtual agents and robots has found similar gender patterns. Girls frequently reacted more strongly to the psychological, social, and relational attributes of technological systems. Girls' affiliation, rapport, and relationship with an agent often affected their perception of the agent and their performance on tasks done with the agent more than for boys. This suggests that making a robot more social and relational might engage girls more, and lead to greater rapport, imitation, and learning. Of course, that might not work for all girls... and the next questions to ask are how we can also engage those girls, and what features the robot ought to have to better engage boys, too. How do we tune the robot's social-relational behavior to engage different people?

More to relationships than gender

There's also a lot more going on in any individual or in any relationship than gender! Things like shared interests and shared experiences build rapport and affiliation, regardless of the gender of those involved. When building and maintaining kids' engagement and attention during learning activities with the robots over time, there's a lot more than the robot's personality or gender that matters. Here's a few I think are especially helpful:

- Personalization to individuals, e.g., choosing stories to tell with an appropriate linguistic/syntactic level,

- Referencing shared experiences like stories told together and facts the child had shared, such as the child's favorite color,

- Sharing backstory and setting expectations about the robot's history, capabilities, and limitations through conversation,

- Using playful and creative story and learning activities, and

- The robot's design from the ground up as a social agent—i.e., considering how to make the robot's facial expressions, movement, dialogue, and other behaviors understandable to humans.

Bottom line: People relate socially and relationally to technology

When it comes to the design of relational technology, the bottom line is that people seem to use the same social-relational mechanisms to understand and relate to technology that they use when dealing with other people. People react to social cues and personality. People assume gender (whether male, female, or some culturally acceptable third gender or in-between). People engage in dialogue and build shared narratives. The more social and relational the technology is, the more people treat it socially and relationally.

This means, when designing relational technology, we need to be aware of how people interact socially and how people typically develop relationships with other people, since that'll tell us a lot about how people might treat a social, relational robot. This will also vary across cultures with different cultural norms. We need to consider the ethical implications of our design decisions, whether that's considering how a robot's behavior might be perpetuating undesirable gender stereotypes, challenging them in positive ways, or whether it's mitigating risks around emotional interaction, attachment, and social manipulation. Do our interactions with gendered robots change to how we interact with people of different genders? (Some of these ethical concerns will be the topic of a later post. Stay tuned!).

We need to explicitly study people's social interactions and relationships with these technologies, like we've been doing in the Personal Robots group, because these technologies are not people, and there are going to be differences in how we respond to them—and this may influence how we interact with other people. Relational technologies have a unique power because they are social and relational. They can engage us and help us in new ways, and they can help us to interact with other people. In order to design them in effective, supportive, and ethical ways, we need to understand the myriad factors that affect our relationships with them—like children's gender.

—

This article originally appeared on the MIT Media Lab website, August, 2019