Is belief in God unjustified?

As a part of my recent philosophical wanderings, I'm reading Kai Nielsen's 1985 book Philosophy & Atheism. He wants to show that belief in God is unjustified.

This is the fifth and final post in the series. I encourage you to read Part I, Part II, Part III, and Part IV if you haven't yet.

Loose ends

The remaining chapters of Nielsen's book take a broad look at some of the common concerns and objections people have to atheism, including religious ethics versus humanistic ethics, and religion and rationality.

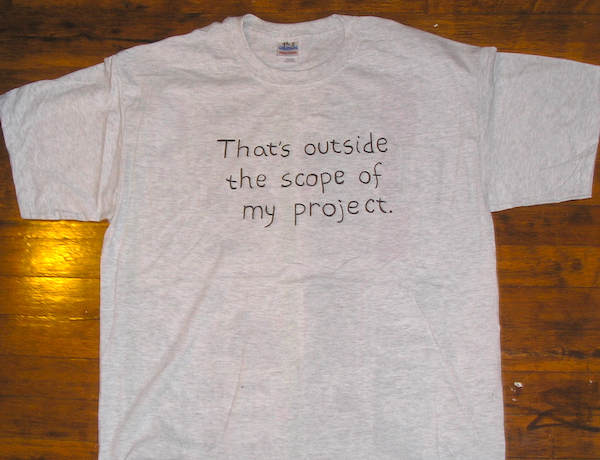

I'm not going to summarize these chapters in depth. Nielsen (and others) have written entire -- and more recent -- books on these topics, which at some point perhaps you'll see me read and discuss here.

Instead, I've collected up miscellaneous notes on some of Nielsen's smaller but still interesting points -- his thoughts on agnosticism, discussions of science and religion, anthropomorphic deities. Let's start with...

Against agnosticism

Nielsen spends one chapter discussing whether agnosticism is a reasonable alternative to either theism or atheism. He proposes, paraphrasing T. H. Huxley, that "we ought never to assert that we know a proposition to be true or indeed even to assent to that proposition unless we have adequate evidence to support it" (p. 56). Are we justified in asserting the truth of propositions about God's existence or non-existence? He argues that we are, and that to take an agnostic stance is to accept the possibility that 'God' has a coherently specifiable referent -- which he argues is not the case.

Science and religion

Also in the chapter on agnosticism is a discussion of how, even with a sophisticated analysis of religion and the assumption that religions are making truth-claims about the state of things, there exist numerous conflicts between science and religion. E.g., many Christians take "as central to their religion that Christ rose from the dead and that there is a life after the death of our earthly bodies" (p.64); these claims don't generally line up with our scientific understanding of the world.

Widely accepted now is the view of the Bible and Bible stories as mythical and poetical; the stories, such as those about demons and Jonah in the whale's belly, should not all be taken literally. But how far, asks Nielsen, should we extend this?

"Are we to extend it to such central Christian claims as 'Christ rose from the Dead,' 'Man shall survive the death of his earthly body,' 'God is in Christ'? If we do, it becomes completely unclear as to what it could mean to speak of either the truth or falsity of the Christian religion. If we do not, then it would see that some central Christian truth-claims do clash with scientific claims" (pp. 64-65).

Nielsen suggests that atheists and agnosticists generally answer this by saying either (a) these religious utterances do not function as truth-claims at all, or (b) science and religion clash. In the case of (b), scientific knowledge is to be preferred as a method of fixing belief because it is more reliable. If there is good scientific reason to suggest that people cannot be resurrected when they die, then we have a strong reason to reject the Christian claim that "Christ rose from the Dead." We could, alternatively, reject the scientific beliefs in favor of the religious ones, but more often is it the case, suggests Nielsen, that scientific understanding drives people toward atheism or agnosticism.

Nielsen discusses several counters to this argument, such as beliefs in miracles, which he defines as events of divine significance that are exceptions to at least one law of nature, noting that scientific laws are falsified only by classes of experimentally repeatable events.

The cool thing about anthropomorphic deities

Nielsen notes that the "anthropomorphic deities of the various cultures are tailor-made projectively to meet the anxieties and emotional needs of their members" (p. 116) Two of his examples: Eskimos see Sedena, a female god who lives in the sea and controls storms, weather, and sea mammals. Israelites see Yahweh, a ferocious male god of the desert who protects the Israelites from alien peoples. Cultural preoccupations are projected onto the universe, and stories are created about the deifications.

He spent a while early on dicussing why one ought not believe in anthropomorphic deities.

Philosophy's role in theology

Nielsen takes some time to question whether or not philosophy has any business at all criticizing, refuting, constructing, or justifying theological systems. The claim is that philosophy is a conceptual inquiry and can evaluate the logic of theological arguments but not their truth.

You're not going to be surprised at what Nielsen argues -- after all, he's a philosopher who has just written an entire philosophy book about theology. Philosophy does have a role to play, he says, and that role is not as a neutral bystander. Rather, philosophy is at the heart of theology. It is the basis on which fundamental religious concepts, claims, revelations, and so on are developed; philosophical criteria such as validity, intelligibility, and truth must be referenced in determining what portions of theology are genuine.

I agree with Nielsen here.

So my question for you is this: Which arguments and philosophies should I read next?